Wrinkles come with age – and for most of us they are unwelcome guests. Sunlight is a well-recognized cause of wrinkles. Slowly adding up over time. we pay the price of our past hours in the sun, as year by year our skin accumulates wrinkles. And just as nothing is fairly distributed in life, so, too, sun-induced wrinkles come sooner and with more intensity to some of us.

The unpleasant discovery of new wrinkles can begin quite early in life for those of us with lightly pigmented skin, and especially for those who are red-heads. The cautionary tales we hear about sun exposure and wrinkles are true, of course, as are the far more serious concerns about sun-induced skin cancers. But we should not equate sun-damaged or ‘photoaged’ skin – the aging that is produced by ultraviolet light – with chronologically or ‘intrinsically-aged’ skin – the aging that comes to all with the passage of time. Age itself does take its toll on skin, but it does so in a manner less obvious to the eye than the wrinkles that are formed by a life in the sun.

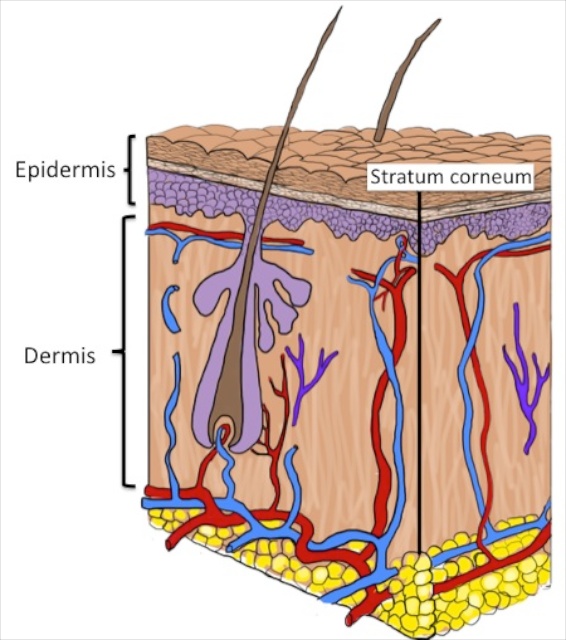

The most obvious manifestation of photoaging is the destruction of the elastic tissue network in the upper part of the dermis; this damage results in what we perceive as the coarse wrinkles around our eyes and in other sun exposed sites. And new pigmented blemishes – large freckles or the so called “age spots” – begin to populate sun exposed regions.

The wrinkles that come with age alone are more subtle. The outer compartment of the skin, the epidermis becomes thinner, because it generates new cells more sluggishly than when it was young. The thinner epidermis imparts a fine, ‘cigarette paper’ quality to the skin. This type of wrinkling is best appreciated by looking at body sites less often exposed to the sun, such as the buttocks. Also with age, the epidermis loosens its attachments to the underlying dermis, such that the skin tears more readily with minor trauma.

Readers of this blog are now familiar with the notion that the skin’s barrier to water loss – its ability to hold our body water inside and to prevent its evaporation into the atmosphere – is the most essential function of the skin. With age the competence of the skin’s permeability barrier also slowly declines. The earliest sign of loss of barrier capacity begins around age 50, when the surface pH of the skin rises. Normally the skin surface is acidic – it has a low pH. It requires effort for the epidermis – which like the rest of the body has a nearly neutral pH – to acidify the stratum corneum. And so with aging, this ability declines, and the stratum corneum becomes less acidic. And this increase in stratum corneum pH in itself can compromise the effectiveness of the barrier.

Then, with more advanced age, skin barrier function declines still further, as the rise in pH is compounded by reductions in the ability of the epidermis to generate or synthesize the water-proofing fats or ‘lipids’ used to form the barrier. The aged epidermis is becoming sluggish not only in the production of new cells but its lipid synthetic factory also is winding down. The result is a thinner barrier layer – both a thinner stratum corneum – and also a thinner coat of water-repellant lipids around the cells.

Among the lipids so affected, the most profound decline is in cholesterol. This may seem odd; that is, the idea that skin becomes deficient in cholesterol, when so many of us need to take medications because the cholesterol level in our blood is too high. But skin – or rather to be precise – the epidermis is on its own path, when it comes to the procuring the lipids it needs for the barrier. With the exception of some essential fatty acids, like linoleic acid that must obtained from the diet, most of the lipids used to form the skin barrier are made by the epidermis itself. This is particularly true of cholesterol: the cholesterol in the lamellar membranes of the stratum corneum was manufactured by the skin. So while your blood cholesterol can rage out of control, your skin at the same time may be deficient in this essential lipid.

Photoaging makes matters even worse for the aged barrier – chronic sun exposure doesn’t just produce wrinkles, it further compromises the skin barrier. Does this matter? Are there consequences of the decline in skin barrier function as we age? The answer is yes, indeed!

The increase in skin surface pH alone makes it more likely that the skin will be colonized or invaded by pathogenic microbes, because the normal acidic pH of the skin surface is our first line of defense against microorganisms. The higher pH not only causes the barrier to become more leaky, but it also results in a stratum corneum that is less cohesive. In other words, it produces a weaker skin that has a tendency to tear with friction or trauma. The sub-optimal barrier of aged skin means that not only will water leak out of the body more readily, chemicals applied to the skin will more readily gain entry. The elderly may be more susceptible to poison ivy or poison oak, because these and other antigens can more readily penetrate across the weakened stratum corneum.

This increased absorption across aged skin applies not only to noxious substances like allergens or toxins, but also to potentially beneficial agents, like topical medications. As some of these drugs will penetrate more easily, a higher risk of toxic side effects may also occur. From a practical point of view, older individuals may need less of a topical agent than the manufacturer recommends, because the preclinical testing may have been performed only on younger adults.

Severe dry skin, or ‘winter itch’, is a very common problem as we get older. Perhaps most importantly, the elderly have a greater tendency to develop eczema or eczema-like rashes. This tendency can be turned into an actuality if the fragile skin barrier is further are stressed by the low humidity indoors during winter or by frequent bathing with harsh soaps. The elderly who previously had problems with atopic dermatitis are particularly vulnerable. And many will suffer from a particularly symptomatic dermatitis, called nummular eczema. This intensely itchy rash represents the summation of the barrier failure brought on by age coupled with colonization with pathological microorganisms like Staph. aureus, and often compounded by other factors (such as, a low humidity, over bathing, and/or psychological stress).

When faced with the implacable forces of an intrinsically-aged epidermis – what is the remedy? Hydrating creams and ointments certainly can help, but they are not ideal because most are based on non-physiologic lipids. Ideally, aged skin would be treated with a mixture of physiologic lipids containing a balanced formulation of the three key classes of stratum corneum lipids and in which cholesterol predominates. But alas, such an ideal product is not currently on the market. It is best to avoid many lotions, because they often exert a net drying effect on the skin. Decrease the frequency of bathing, if possible, and when you do bathe, use a mild product – non-soup-based surfactants or ‘syndets’ may be less irritating -, and a cool-to-tepid water temperature. To address the acidity problem, seek out acidic pH cleansers and moisturizers. For more information on skin care, sigh up to receive our free booklet, “Taking Good Care of Your Skin”.

If some one desires to be updated with hottest technologies

afterward he must be visit this website and be up to date

all the time.