Know anyone with psoriasis or some type of eczema? Most of us do. These are common skin conditions: one child in five has atopic dermatitis; 2% of the population has psoriasis. That’s a lot of people! Treatment is an ongoing battle for many who are affected by one of these conditions. They must often – sometimes several times daily – apply various creams and ointments to their skin, because the mainstay of treatment for these common skin disorders is still some form of topical therapy. Then, consider the issue of dry skin. This is an extremely common affliction, especially during winter months and as our skin gets older.

As those of us who suffer from one of these conditions search for effective skin creams and lotions, we fuel a large cosmetic and pharmaceutical industry that provides us with many choices. But just as one would not put diesel fuel into the tank of a car manufactured to run on gasoline, so too, it is important to put the right stuff on the skin.

We now know that having one of these skin conditions means that there is a problem with the skin barrier. Treatment of the barrier failure is an important part of healing the dermatitis and preventing relapses. Indeed, many products now tout their ability to restore or repair the skin barrier.

The task consumers face of sorting through the number and variety of products that claim to restore the barrier can be overwhelming, and the din of their marketing can be deafening. Indeed, ‘barrier repair’ has become something of a buzz word in the industry, yet the science behind these claims is all too often lacking. To assist in the reader in interpreting what the various products have to offer, we offer the following classification of strategies to repair the skin barrier.

1) Dressings

Dressings are specialized bandages. They are primarily used to cover wounds and thereby, to accelerate healing. Although they are not a front-line strategy in the treatment of inflammatory skin disorders, like atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, it is helpful to consider how they work, because they can help us to understand how some of the other barrier repair modalities operate.

There are two general types of dressings depending upon whether or not they are air tight; that is, whether they are ‘vapor-impermeable’ or ‘vapor–permeable’. It should be understood, however, that the latter category – vapor-permeable – is relative, because these dressings allow the passage of some water vapor. In other words, they vary in their capacity to occlude or slow water movement. While all dressings are primarily used to promote the healing of wounds, they can also increase the penetration and, therefore, the efficacy of topical medications, such as cortisone or steroids (or more precisely, ‘corticosteroids’).

Dressings can also be highly effective in treating inflammatory skin conditions, like psoriasis. As they artificially improve barrier function by covering and occluding the skin, they simultaneously ‘turn off’ the pro-inflammatory signals that the leaky epidermis sends out. When the barrier is artificially restored by an occlusive dressing, these signals are not released, because the epidermis senses that its barrier is working normally.

But this strategy is actually a ‘trick’ played on the skin, because these dressings do not fix the underlying problem with the barrier. The signals released by a damaged barrier not only call in the white blood cells that fight infections, they also direct the epidermis to repair its own barrier – they direct it to make and secrete more barrier lipids. But when a psoriasis lesion is covered with a dressing, the epidermis has not actually been healed – the problem was just ‘covered over’, as it were (like throwing a blanket over an unmade bed). Nonetheless, this approach certainly works to shut off inflammation – and sometimes psoriasis plaques can even disappear with this type of ‘cover-up’ repair therapy.

2) Ointments, creams and lotions not ‘natural’ to the skin

These products are the commonly used emollients made up of fats (or ‘lipids’) that are not normally present in our bodies. These include preparations based upon petroleum jelly, a product that is distilled from petroleum, or upon lanolin, which derives from oils that coat the wool of sheep. Because these lipids, petrolatum and lanolin, are not made in humans, they are considered ‘non-physiologic.’ Nonetheless, they are cheap, readily available and widely deployed in skin care and cosmetic products, as well as in the vehicles that deliver topical prescription drugs through the skin.

These non-physiologic ingredients basically function much like vapor-permeable membranes, in that they temporarily coat the surface of the skin and slow the outward movement of water. In other words, they, too, trick the epidermis into thinking its barrier is working better – and to that extent, they can shut off signals for inflammation. But, alas, they also can shut down the skin’s own barrier repair processes, so that when they wear off – which they do in a few hours – the leaky barrier with all its attendant complications is still there.

The crux of the problem here is that these agents require frequent reapplications to be effective, and when they wear off, the underlying barrier defect persists.

3) Ointments and creams based upon ‘physiologic’ lipids

These agents represent a newer and more expensive category of materials in which the ingredient lipids are similar to those that are normally produced by the skin in forming its permeability barrier. In other words, they are composed of lipids that are physiologic to the skin. They are now being deployed in skin care products to reinforce a normal barrier or to correct the abnormal skin barrier of conditions like atopic dermatitis. These physiologic lipids encompass three different types of lipids, namely cholesterol, free fatty acids and ceramides.

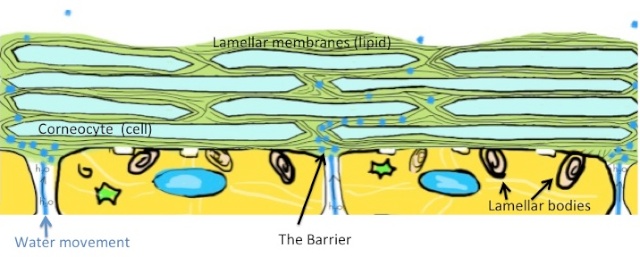

When physiologic lipids are applied to the skin surface, they don’t just sit there, forming a film on the surface, as do non-physiologic lipids like petrolatum. Instead, physiologic lipids penetrate through the stratum corneum. Then, they are taken up by the living epidermal cells below and packaged into a secretory vesicle (the ‘lamellar body’), along with the lipids that the epidermal cell manufactures. The contents of these vesicles are subsequently secreted back into the stratum corneum to form the lamellar membranes that surround and coat the cells of the stratum corneum, and, thereby, water-proof the skin. These lamellar membranes form the permeability barrier of the stratum corneum.

In normal stratum corneum, the three lipid classes are present in an approximate 1:1:1 ratio, molecule for molecule. Each of the three lipids is equally important; i.e., you need all three to have a well functioning barrier; we have termed this the ‘critical mole ratio’. If one applies just one or two of the lipid classes to damaged skin, repair processes are delayed – and the barrier actually gets worse.

We have identified an ‘optimal’ ratio, 3:1:1′ that accelerates barrier repair in normal skin. For treating skin conditions like atopic dermatitis and aging skin the choice of which of the lipids should predominate differs. In atopic dermatitis, ceramides are the best choice, while in aged skin, it would be cholesterol.

Unfortunately, the majority of skin care products that are currently being marketed as barrier repair formulations for dry skin or for diseases like atopic dermatitis and psoriasis do not contain all three lipid classes of physiologic lipids. Or, if all three are present, they often are present in the wrong balance or ratios.

Also, and most unfortunately, the consumer has little to guide him in ascertaining which ones among all the products that tout the words, ‘barrier repair’, are truly effective. Typically, there is little in the way of scientific reports to back up the company’s claims. ‘Barrier repair’ is used more as a buzz word, than as a verifiable claim. It is virtually impossible for the consumer to discover whether the preparation contain all 3 classes of key lipids and if they are present in the correct ratio, to say nothing of whether they contain adequate amounts of these physiologic lipids. (For more on skin care products, sign up to receive our free booklet: Taking Good Care of Your Skin.)

4) Agents that boost or augment the formation of the barrier by the epidermis

Some vitamins, antioxidants, botanicals and other types of natural ingredients, such as oils containing essential fatty acids or ceramides, as well as hyaluronic acid, lactic acid or urea, can stimulate lipid production by the epidermis, and/or function as physiologic lipid ingredients within the lamellar membranes. In most cases, these ingredients have been added to topical formulations based upon theoretical considerations or upon evidence that they boost lipid production or epidermal differentiation in tissue culture experiments or in laboratory animals. Products that contain nicotinamide, intended to boost the production of ceramides, are also touted as ancillary therapy for atopic dermatitis. Yet, very few of these ingredients have actually been tested in clinical practice.

Primrose oil, and more recently, borage oil, containing the essential fatty acid, gamma linoleic acid, have been advocated for the treatment of atopic dermatitis, but evidence of their efficacy is limited. Nonetheless, further explorations in this area hold promise for the treatment of barrier-driven skin disorders. For example, we have recently shown that urea enhances barrier function and antimicrobial defense when applied to human skin .

THE BOTTOM LINE

Although we have considered these four approaches as separate strategies to repair the barrier, formulations can contain multiple ingredients from each of the last three categories. Indeed, a highly effective topical product available by a doctor’s presciption for the treatment of atopic dermatitis, EpiCeram® emulsion contains not only a ceramide-dominant (3:1:1) mixture of physiologic lipids, but also small amounts of petrolatum, glycerol, and specific fatty acids that stimulate lipid production. This product is based upon research that came out of the Elias laboratory.

I do not know if it’s just me or if perhaps everyone else

encountering issues with your website. It appears like some of the text in your posts are running off the

screen. Can somebody else please comment and let me know if this

is happening to them as well? This may be a issue with my internet browser because I’ve had this happen before.

Thanks

We haven’t heard this complaint from others, but we will post your concern.