A: You are right: skin is indeed made up of 3 distinct layers, each with strikingly different characteristics and functions.

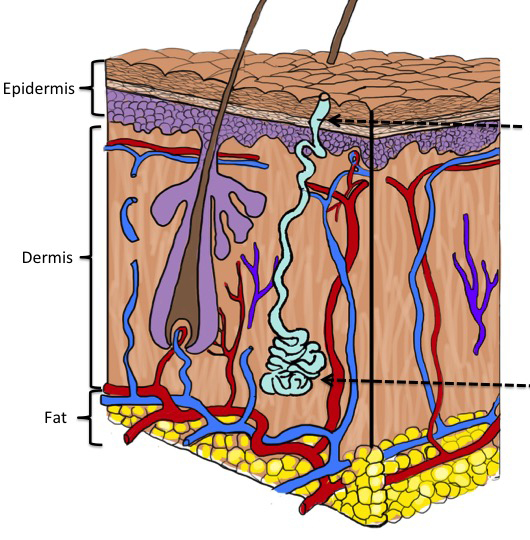

These layers are: epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fat. Skin diseases often primarily localize to one of these layers, which can be important for their diagnosis. Understanding the structure of skin also helps us to take better care of it.

Epidermis

Although the epidermis is by far its the smallest compartment, we like to think of epidermis as the ‘business end’ of skin.

The outermost layer of skin is the epidermis. The epidermis is responsible for producing and maintaining our barrier between the inside and the outside worlds. These critical barriers are several. First and foremost is the skin’s permeability barrier, which protects against the outward loss of our body’s water, while at the same time preventing the inward invasion of most everything else – from bath water to foreign chemicals. Also vital for survival is its antimicrobial barrier, which keeps microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi, etc.) in our surroundings from invading and infecting our tissues. It also provides a barrier against damaging rays of sunlight that could kill its cells, or wound their DNA, sending them along the path to fatal cancers. And in concert with the next underlying layer, the dermis, epidermis erects a mechanical barrier against traumatic injuries.

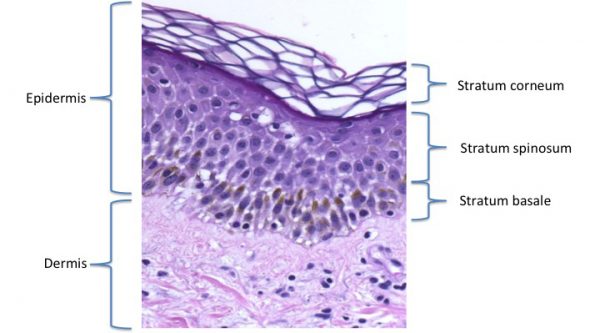

Epidermis, too, has several layers.

Although the epidermis is quite thin, relative to the full thickness of skin, it, nonetheless, is divided into several of its own layers. These are most easily understood from the inside-out. Its innermost or bottom layer is called the basal cell layer, or if you prefer latin, ‘Stratum basale’. This layer houses the mother (or ‘stem’) cells of the epidermis. In addition to housing the cells, ‘keratinocytes’ that will ultimately generate the stratum corneum, epidermis is home to a family of immune cells, called ‘Langerhans cells’ charged with early recognition of foreign antigens and pigment producing cells, ‘melanocytes’.

After stem cells give birth through cell division, their daughter keratinocytes move outwards through several additional layers, progressively becoming more mature, more specialized. In scientific parlance, they ‘differentiate’. Scientists divide the layers of this progression by various terms (spinous or granular), somewhat analogous to our terms, (children vs. teenagers) depending on where they are in this process. The final, outermost layer produced in this epidermal sequence is the stratum corneum. It is there, in the end product of this process of maturation and differentiation – the stratum corneum – that the all-important permeability barrier resides. (For more on the structure and function of the stratum corneum, sign up to receive our free special report, Primer on the Skin Barrier).

Dermis

The next layer below the epidermis is the dermis. The dermis provides strength and resiliency to the skin, and serves as the conduit for delivering nutrients and receiving information. It is much larger than the epidermis and mostly filled with fibrous tissue, (collagen and elastin), and a spongy matrix in between. These fibers give skin much of its properties of mechanical strength and elasticity. In contrast to the epidermis, which is packed with cells, the dermis has few cells. ‘Fibroblasts’ are scattered sparsely about, to manufacture these fibers and matrices. Blood vessels course through the dermis delivering oxygen and nutrients to the epidermis, and carrying away its wastes. Cells of the immune system traffic through these vessels to sites of injury, where they recognize and react to foreign antigens and infectious organisms. A rich supply of nerves also course through the dermis, to send to and receive information from the epidermis. The epidermis also sends offshoots – hair follicles and sweat glands – which for the most part reside in the dermis.

Fat layer

While in our contemporary world of caloric excess, we may view our subcutaneous fat as an unwanted part of us, it, too, has important functions.

Below the dermis lies that highly variable compartment, individual to individual, of adipose tissue – or ‘subcutaneous fat’. It provides insulation against the loss of body heat, and stores energy that can be mobilized in time of need – when crops fail or when hunters return empty-handed.

Another reason why the different layers of skin are important.

These 3 skin layers also differ in their origin. Epidermis develops out of the embryonic ectoderm – the outer layer of the embryo – while dermis and the subcutis are mesodermal in origin. Early in embryonic development, an invagination forms in the ectodermal sheet. This closes to form a tube – the neural tube – which in turn gives rise to the nervous system and brain. The mesoderm is the middle layer, lying between the outer ectodermal layer and the inner endoderm, which develops into the gut and lungs. In addition to the dermis, the mesoderm also develops into the musculoskeletal and circulation.

It is this common ectodermal origin of both skin and brain that accounts for the many brain-like features of skin – something that we will discuss in future posts. It may also underlie the recently described association of autism and atopic dermatitis.

Leave a Reply