In another post, we consider how a group of inherited skin conditions in which most or all of the body is covered with scales have helped us to understand the how skin sheds its outermost cells. Because visible scales are such a prominent feature, it is not surprising that this family of skin disorders, called ichthyosis, have taught us a great deal about the process of desquamation. But it was not anticipated that they could also teach us about the permeability barrier – that is, skin’s ability to prevent the outward escape of our precious body water. Yet, one common thread that has emerged from research is that while scaling is most visible feature of ichthyosis, all types possess another and probably more important feature in common, namely, failure of the skin barrier.

Readers of this blog are familiar with the pivotal role the skin plays in preventing us from withering like raisins or prunes as we go about our lives. We – like other living beings – are essentially vessels of water. We are 80% water – and yet we live on dry land and are surrounded by dry air. It is our skin’s permeability barrier that holds our body water inside and that barrier resides in the outermost layer of skin, the stratum corneum. In short, the skin in ichthyosis is unable to prevent water loss as it should.

This phenomenon – barrier failure with thicker skin – is actually counter-intuitive. One would think that that if there is more stratum corneum than normal, as is the case in most of the ichthyoses, the barrier should – if anything – be better than in normal skin. But in fact, even in the absence of inherited conditions like ichthyosis, the thickness of the stratum corneum does not correlate with effectiveness of the skin’s barrier.

Take our palms and soles for example. They have on the order of 100 layers of outer skin cells or ‘corneocytes’, while the skin on our back or chest has only about 30 layers. Yet, palm and sole skin is much leakier than skin elsewhere on the body.

Ichthyosis offers scientists a way to try to understand this puzzle: why a thicker stratum corneum does not necessarily provide a better barrier. The discovery of the genes that cause most of these disorders has taught us how different components of the stratum corneum work together to generate a competent barrier to water loss.

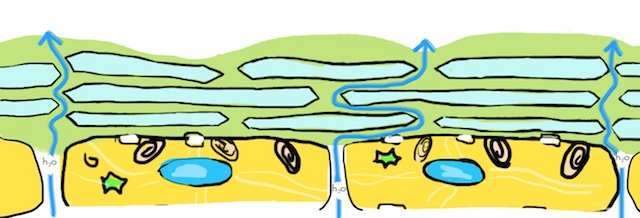

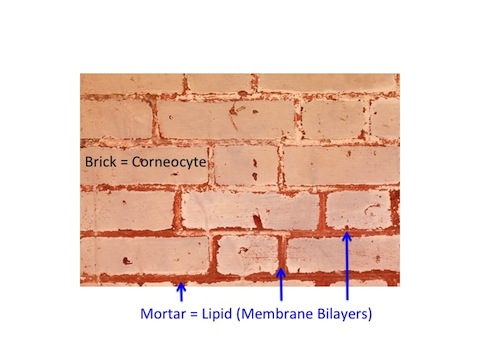

To understand these revelations we need to reconsider the bricks and mortar model of the outermost layer of skin, the stratum corneum. The skin cells of outermost layer of the epidermis, the stratum corneum, are the ‘bricks’. The ‘mortar’ is made up of fats or ‘lipids’ laid down in sheets or ‘lamellar membranes’. Multiple layers of membranes wrap around and envelope these skin cells or ‘corneocytes’. And multiple layers of corneocytes with their lipid wraps make up the wall that is the stratum corneum.

It is the interposition of this layer upon layer of water-repellant or ‘hydrophobic’ lipids between the water-saturated interior of the body and the drier outside atmosphere that prevents the loss of precious body water to the outside world. The corneocytes are needed to provide a scaffold for the lipids. And it is this reduplication – multiple layers of cells, each cell with its lipid wrap – that provides an ‘insurance policy’ for the barrier.

In some of the ichthyoses, the genetic mutation affects the production of one of the lipids that make up the lamellar membranes. Then, because the membranes are missing a key ingredient, they become disorganized. They develop pores, swiss cheese-like, that allow water to percolate outward. The problem here is with the poor quality of the lamellar membranes.

In other ichthyoses, the correct lipids are made by the skin cells, but there is a problem with the delivery system. The lipids remain trapped inside the corneocytes or ‘bricks’ where they are not available to form the lamellar membranes that coat the outside of the cells. With a deficiency in the quantity of lamellar lipids, there is little to prevent water from leaking between the skin cells to the surface where it evaporates away. In both of these instances, with either too little lipid or the ‘wrong’ lipids, the result is the same – an ineffective permeability barrier.

In still other cases the genetic mutations causing ichthyosis affect the proteins that form the outer surface or shell of each corneocyte (the ‘cornified cell envelope’). These mutations compromise the ability of the corneoctye to function as a scaffold for the lamellar membranes. Without their scaffold, the lamellar membranes are disorganized – once again forming ‘swiss cheese’ – and the barrier is rendered ineffective.

Over 40 different genes have been found to cause a form of ichthyosis – the functions of these genes covers a very broad range of cellular operations. Indeed, it looks as though almost any mutation that affects the metabolism of the epidermal cell, is likely in the end to produce ichthyosis. Another way of looking at that likelihood is to consider that the most important function of the epidermis is to generate a competent barrier to water loss. A mutation that causes an epidermal abnormality is likely to also cause a barrier abnormality. That is how central the barrier is to the epidermis.

In some instances, the barrier failure in ichthyosis can be life threatening. Massive amounts of fluid can leak out – particularly in infants and newborns with severe forms of ichthyosis, like Netherton syndrome or Harlequin ichthyosis. This can lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalances, with high sodium levels or ‘hypernatremia’. Babies are particularly vulnerable to these complications of ichthyosis, because of they have a large surface area relative to their small body volumes from which they can loose precious body water.

Barrier failure can also lead to growth failure, because as water evaporates it takes along with it calories, as heat of evaporation. Actually, we all know this. This is why we sweat – to eliminate excess body heat and cool our overheated interiors by the evaporating of watery sweat at the skin surface. But sweating is something our body chooses to do –when it needs to regulate our internal temperature. In contrast, the heat lost through a leaky skin barrier is not regulated; it continues whether we need to be cooled or not.

Babies with ichthyosis are also particularly vulnerable to the consequences of unwanted loss of calories through heat of evaporation. This is because they are growing so rapidly. Growth is so demanding in the first months of life, that every calorie consumed is needed to fuel this factory of growth. Therefore, babies with a severe barrier impairment due to their ichthyosis – babies with Netherton syndrome, for example – may experience extreme, even life-threatening failure to thrive, due in large part to an inability to compensate for caloric losses from their skin. These babies need extra fluid intake to compensate for their leaky skin barriers; and they need extra calories to compensate for those lost through heat of evaporation. Satisfying their fluid requirements and nutritional needs can be a challenge to the parents and physicians who care for these infants.

For a closer look at how the permeability barrier works, sign up to receive our free booklet, “A Primer on the Skin Barrier“.

Good blog you’ve got here.. It’s difficult to find high quality

writing like yours nowadays. I seriously appreciate

individuals like you! Take care!!