In two earlier posts we discussed why atopic dermatitis is becoming more prevalent and what is known about the genetic underpinings of this common disorder. In this installment, we look at how the most common gene associated with atopic dermatitis acts to produce the skin condition.

It has known for decades that the skin has a “sour surface”. The pH of the skin surface is acidic (~5), while our cells and blood have a nearly neutral (~7.4) pH. This low surface pH is assumed to be critical to discourage the growth of bacteria and other microorganisms. Indeed, the microbes that normally inhabit our skin (our so-called ‘normal skin flora’) thrive in an acidic environment, while the pathogens that cause serious infections, such as Staphylococcus aureus and the streptococci, do not. These ‘bad bugs’ much prefer a higher pH. Undoubtedly, the low pH of normal stratum corneum, plays an important role in our defenses against infections. Indeed, the acidic pH of the skin surface can be considered part of our innate immune system.

Atopic Dermatitis: Not Sour Enough

And for people with atopic dermatitis, this part of the immune system is in trouble. In atopic dermatitis, the pH of the skin surface is not as acidic as it should be. Their more nearly neutral surface pH favors colonization by pathogenic organisms, particularly Staph. aureus. Indeed, skin infections with staph or strep are a common complication for individuals with eczema.

Inheriting one of the filaggrin mutations associated with atopic dermatitis sets the stage for problems with stratum corneum pH. Normally, the breakdown of filaggrin in stratum corneum releases a number of small molecules that are highly acidic, thereby supplying the tissue with a source of protons and lowering the pH.

But the ability of a low pH on the skin surface to prevent infection is only one of the benefits of our ‘sour surface’. An acidic pH is also important: 1) for optimal function of the permeability barrier; 2) for the tight cohesion of the cells of stratum corneum; and 3) to prevent the inflammation caused by the release of pro-inflammatory molecules called ‘cytokines’. The basis for abnormal function in all these cases is an increase in the activities of a group of enzymes, called ‘serine proteases’. A low or acidic pH holds these proteases in check, but as the pH becomes closer to neutral, they become more active.

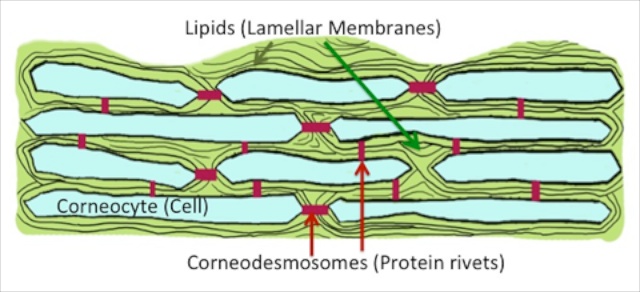

These proteases disrupt the skin barrier by digesting other enzymes that are needed to generate the lipid types that makeup the fatty membranes that coat the cells of the stratum corneum. These lipid membranes are what keep water inside the body – they are the workhorses of the barrier. Without the proper amount and type of lipids, the membranes are defective and the barrier is leaky. The proteases also chew up the cellular rivets, called corneodesmosomes, that knit the corneocytes together, and thereby weaken the structural integrity of the skin.

These proteases also activate signaling molecules, the pro-inflammatory cytokines, ‘interleukin-1alpha’ and ‘interleukin-1beta.’ Normally, these cytokines are held in an inactive state inside the corneocytes, poised and ready to respond. When the surface of the skin is assaulted in some manner, they are activated by these proteases, which cleave the smaller, active cytokine from the larger, precursor molecule. Once released and activated, they can initiate a cytokine cascade – the production and release of another signaling molecule or cytokine, that in turn activates another down the pathway, and so on, and resulting ultimately in the recruitment of cells of the immune system to the skin. The net result is inflammation.

A low pH in the stratum corneum is therefore critical not only for purposes of antimicrobial defense, but also for normal stratum corneum integrity, for normal barrier function, as well as for the prevention of unwanted inflammation.

How a “Sweet Surface” Provokes Atopic Dermatitis

Filaggrin deficiency in many people afflicted with atopic dermatitis results in a paucity of small acidic molecules derived from the breakdown of filaggrin, and this, in turn, impairs the ability of individuals who inherit this gene to acidify their stratum corneum. The rise in pH in turn activates the serine proteases, leading to: compromised skin barrier function, impaired cohesion of the outer layers of skin, and the development of inflammation. Indeed, if the stratum corneum can be maintained at an acidic pH, inflammation will not develop and the function of the permeability barrier can be restored to normal – at least in the laboratory and in experimental animal models of atopic dermatitis.

The central role of serine proteases in producing the rash of atopic dermatitis is shown most eloquently in a rare inherited type of ichthyosis, Netherton syndrome. This recessively inherited trait is caused by mutations in a gene that encodes a serine protease inhibitor, called ‘LEKTI’. These individuals typically suffer from an atopic dermatitis-like condition, accompanied by a severe defect in skin barrier function. The severity of the rash and barrier abnormality in Netherton syndrome is proportional to the extent of loss of LEKTI (some mutations in the gene produce a greater deficiency in LEKTI), and therefore, to the extent to which serine protease activity is increased.

Netherton syndrome also teaches us that you can develop atopic dermatitis from inherited defects that compromise the structure of the stratum corneumn other than filaggrin deficiency. Indeed, we now know that not just filaggrin mutations and LEKTI deficiency, but also several other inherited abnormalities in unrelated genes that modify stratum corneum structure and function favor the development of atopic dermatitis.

In a future post we will examine new paradigms for the treatment of atopic dermatitis.

Leave a Reply